Gay and lesbian walking tour of South Beach, Miami

Our guide’s name is Deborah and she is holding an umbrella. Deborah clearly knows something we don’t. As we will quickly find out, Deborah knows an awful lot. And not just about the increasingly unpredictable Miami weather.

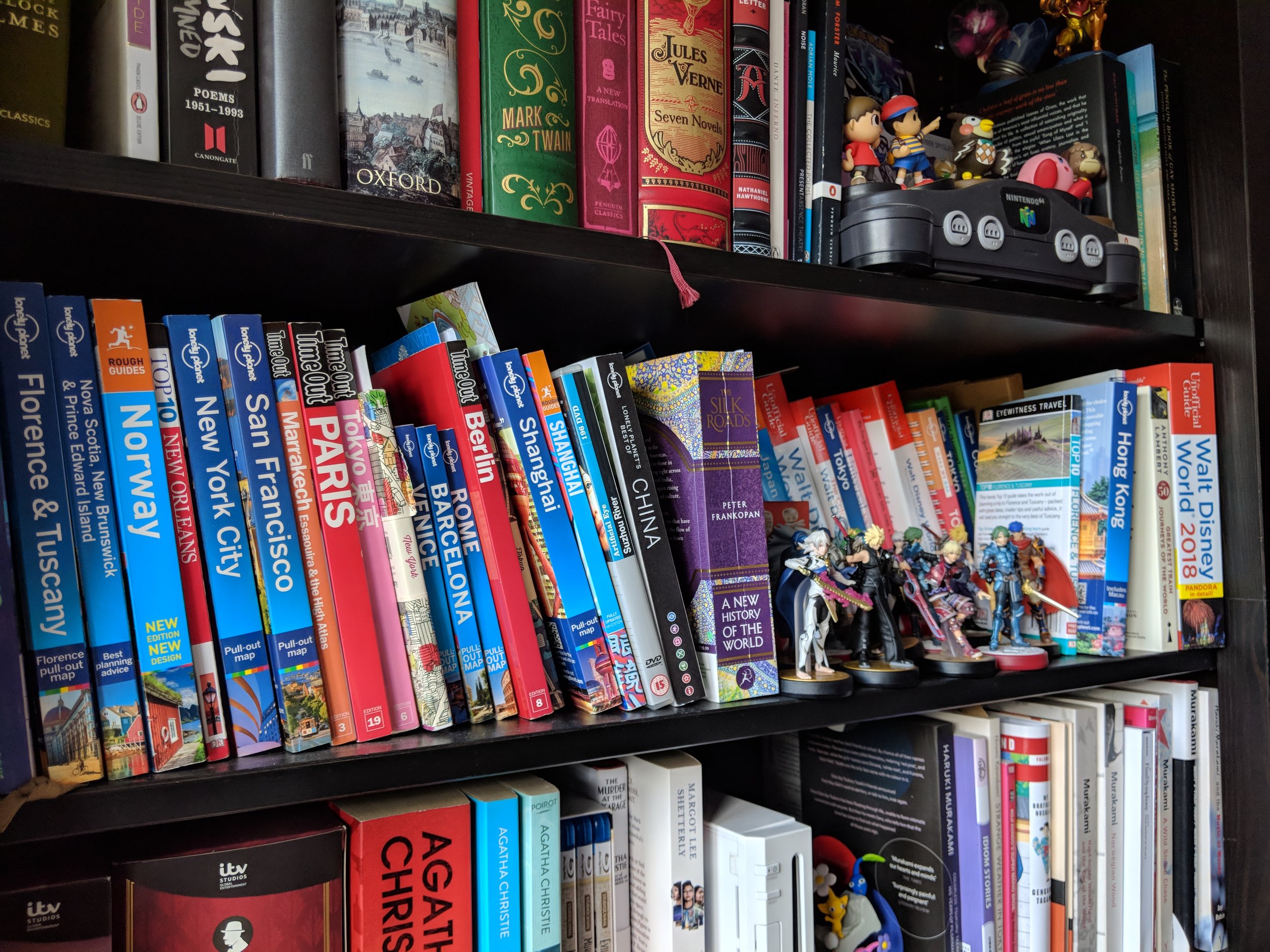

We are here for the Gay and Lesbian Walking Tour, organised by the Miami Design Preservation League, an organisation founded to preserve Miami Beach’s iconic art deco architecture. As the queer history of the city is inextricably intertwined with its architectural heritage, it makes sense that we meet Deborah inside the Welcome Center (sic – we’re in America after all) of the Preservation League. This is a fascinating destination in itself, chronicling the rise and fall, and rise again, of Miami Beach’s fortunes throughout the twentieth century and beyond.

As is usual for us, we’re very early. And so is Deborah. But as the tour has been laid on especially for us, we don’t have to wait around for anyone else so we decide to get underway immediately. “Good idea,” says Deborah, gesturing to the darkening clouds with her umbrella.

Only minutes before it was a typical Florida morning: sunshine so bright it stung our eyes, so humid that stepping out of any air-conditioned space felt like walking into a steam room.

But the sky is bruising before our eyes. We know what that means. We’ve been to Florida in August together a few times and have been able to set our watches by the mid-late afternoon downpours. But today it’s not even lunchtime. “Climate change,” Deborah says. “Even in the time I’ve been living here, I’ve seen a big change in the weather. It’s less predictable than it used to be.”

Deborah has lived in Miami for less than a decade. A retired solicitor, she clearly loves her adopted home city and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of its history – and its meteorology.

The British fell-walker and guidebook author Alfred Wainwright famously remarked that “There’s no such thing as bad weather, only unsuitable clothing.” And it’s true: whilst Deborah is not only armed with an umbrella but also clad in a waterproof, Antony and I are unapologetically dressed for SUMMER. Antony: shorts, tank top, straw hat. Me: pink polo, white shorts.

Recognise the facade? The Carlyle was the setting for The Birdcage, the 1996 queer classic starring Robin Williams and Nathan Lane.

Undaunted by the gathering storm, we pause just around the corner of the Welcome Center so Deborah can give us an overview of the city’s LGBT history. Whilst racial equality was, and to an extent remains, a battleground for Miami Beach, queer inclusivity is almost taken for granted now. However, like most places with a reputation for being queer-friendly, it wasn’t always the case. 1972 saw the city’s first pride parade but an attempt to pass a law banning discrimination against gays and lesbians was shot down in 1977, led by familiar personality Anita Bryant. The backlash ruined her career and didn’t prevent Miami Beach becoming a haven for the LGBT community throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Road signs memorialise some of the people who made South Beach the place it is today. The co-founder of the Preservation League, Leonard Horowitz designed the colour palette that keeps Miami looking pastel-bright to this day. Leonard himself died of complications of AIDS in 1989, a tragically abrupt ending which one encounters all-too-frequently when looking into LGBT history. He was only 43.

But Leonard’s legacy lives on, in the form of the densest concentration of art deco buildings anywhere in the world. Without his intervention, and that of his friend Barbara Capitman, who died only the year after Horowitz, Miami Beach would look very different today. Many of the art deco buildings were constructed quickly in the 1930s. By the 1970s they were crumbling and many were pulled down. Capitman and Horowitz worked tirelessly to preserve what they could and prevented Miami Beach from becoming just another anonymous beachfront resort.

Deborah leads us to the most iconic buildings and their lesser known queer connections. The Breakwater Hotel, for instance, dates back to 1936 but in 1984 its rooftop was crammed with nude models for Calvin Klein’s controversial Obsession campaign, photographed by Bruce Weber. Weber and Klein, both gay icons, have continued to push the envelope of male objectification, giving us something nice to look at but also, along the way, impossibly unattainable beauty standards.

Breakwater Hotel. No nude fashion modelling today.

Another gay fashion icon, Versace, made his home here. His mansion, now a luxury restaurant, draws the mordibly curious. He was assassinated on the front steps in 1997. Consequently, this is the third most photographed house in the USA - after the White House and Elvis’s Graceland. Deborah tells us that some even pose on the steps, face down, in the exact prone position Versace fell, having been shot by Andrew Cunanan. We take the obligatory photograph from the other side of the street and move on.

Where Versace lived - and died. Take a picture and move on.

With her keen weather eye, Deborah suggests we move away from Ocean Drive and traverse the side streets where we will get more shelter once the heavens open. She eyes our attire with a degree of pity but we reassure her than we don’t mind getting a bit wet. She clings to her umbrella as if to say ‘there’s a bit wet… and there’s Miami wet.’

We find out firsthand how wet Miami gets when the inevitable happens only seconds later. We huddle beneath Deborah’s umbrella as she tells us how Michael Mann’s Miami Vice did more good than harm, giving the economy a much needed boost in the 1980s. The association with ‘vice’ clearly didn’t put people off.

NB: Not using ‘wet look’ hair gel. It’s just wet.

When the rain has abated slightly, Deborah weaves us through the streets to find the gay and lesbian locations most people walk straight past without realising their significance. These include one of the few remaining gay clubs: Twist. Gentrification has struck Miami Beach, as it has many historically important LGBT-friendly places.

Another queer-friendly shop bites the dust. Leonard Horowitz’s iconic colour palette still shines proudly however.

Whilst its wonderful that many queer people now feel they can inhabit ‘straight’ spaces without feeling unsafe, it’s also sad that so many queer-targeted businesses are having to close. Either they can no longer afford the rent or their patrons can’t. In Miami’s case, much of the queer clientele has moved north, where property prices are more affordable. Nevertheless, Miami has more than its fair share of rainbow flags. You can argue that any corporation’s choice to adorn their premises with rainbow flags is just a cynical move to capture the ‘pink pound’. But however you look at it, it’s increased visibility. The flags say queers are here and they’re welcome. In my view, this can never be a bad thing, even if everyone, gay or straight, ends up having to spend a fortune just to get a decent cup of coffee (hear me Starbucks?).

Keeping the rainbow flags flying (just about).

A queer-friendly Starbucks inside an erotic art museum. They’re everywhere these days.

Even the former City Hall has been taken over by the LGBT Chamber of Commerce.

But not all of the stops on our tour are quite so demure. Deborah has saved the loudest and proudest until last. The Palace drag club has been around for decades. In 2016 it almost became another victim of a hike in rent but it survived. In 2017, it moved to larger premises on Ocean Drive. It’s one of the most visible (and certainly audible) businesses in this most exclusive of addresses. Famed for its drag brunches, the show spills out onto the road with passers-by inextricably drawn to the tumult, despite (or perhaps because of) the strong chance that they will be ‘read’ by the Palace’s fierce queens.

Bringing LGBT history realness to Ocean Drive.

The Palace itself is housed in one of the most quintessentially art deco buildings in the whole of Miami Beach. It’s tempting to read too much into the Palace’s pre-eminence. Is its prime location indicative of wider society’s increased acceptance of queers? Rather than being pushed to the fringes, they are now at the heart of the community.

But the reality is, queers have always at the heart of every community, as they have everywhere. They’ve just not been able to show their true selves to their neighbours.

There’s still enough glitter on Miami Beach’s surface that even casual visitors can’t fail to gain the impression that this is an important place in LGBT history. But without Deborah’s expertise we would have missed a great deal of it. Her umbrella came in handy too.

Everywhere should have one: a rainbow crosswalk.

The Gay and Lesbian Walking Tour is offered on request. Visit the address below to find out more.